“If you fell down yesterday, stand up today.”

— H.G. Wells

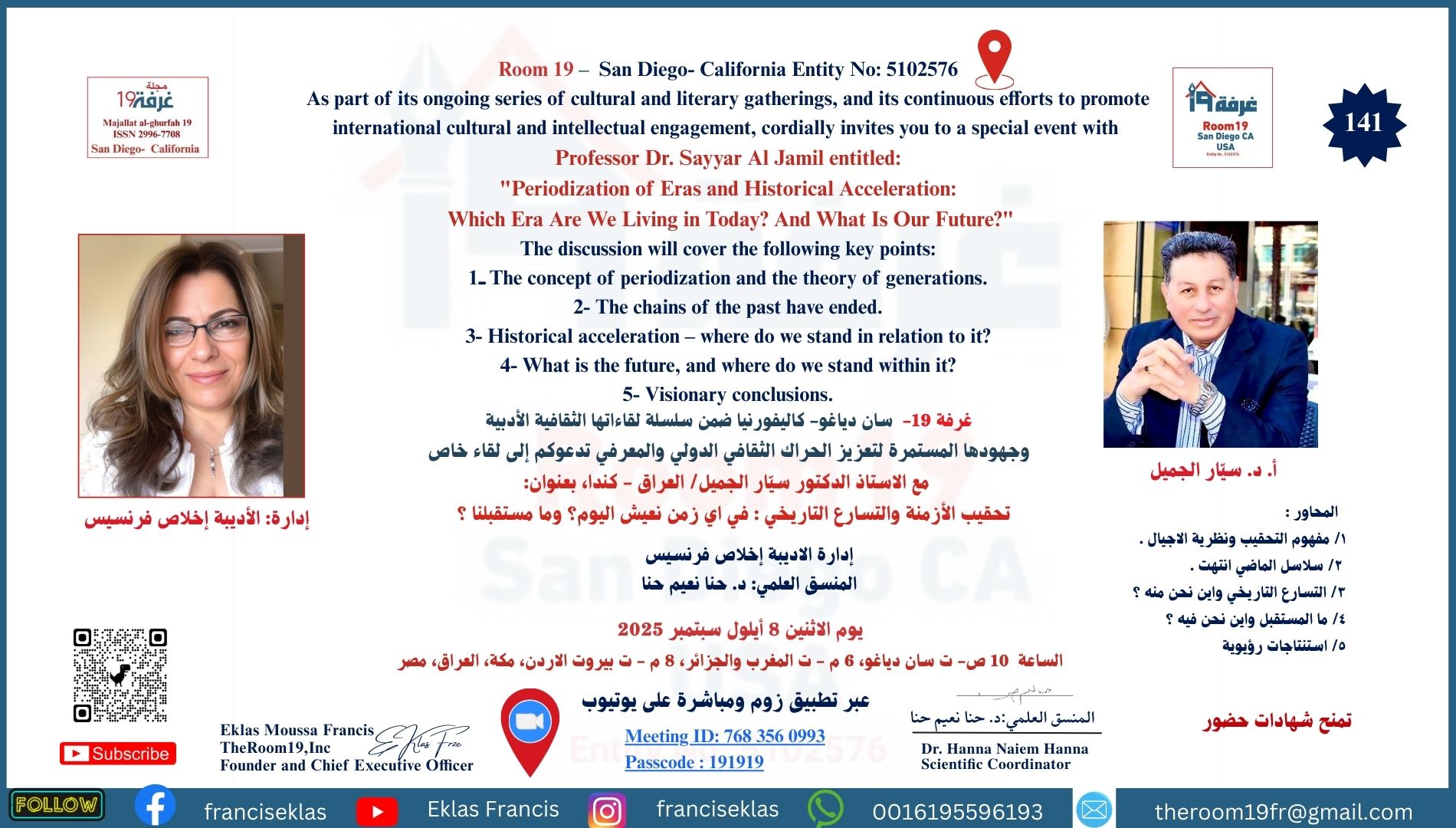

On 8 September 2025 I attended (virtually) a Room 19 presentation with a distinguished Iraqi historian, Dr. Sayar Al-Jamil – (تحقيب الأزمنة والتسارع التاريخي : في اي زمن نعيش اليوم؟ وما مستقبلنا ارؤيوية). There were so many valued questioners, including my friend Dr. Walid Ali from Alexandria (see below), I didn’t get a chance to interject. Here’s my contribution to the debate on historical phases and the controversy surrounding periodization.

Introducing the Topic

Dr. Sayar was perfectly correct to endorse periodization while also cautioning against a lavish devotion to it. The good thing, the necessary thing, about periodization is to understand the basic fact that we can’t comprehend where we are today without understanding how we got there. Once you do this, you understand time as a continuum and that just as there is a past pushing in a certain direction, there is a future, also caused to push in a certain direction. I agree, and very strongly, and I’ll tell you why – science fiction. Watch the latest version of The Time Machine (2002) from H.G. Wells. You have the virtual librarian telling the hero about human beings in this future world, after mankind divided into two subspecies – the Eloi topside and the Morlocks underground. The Eloi are food for the Morlocks, and their central weakness is, as he says, “Look at them. They do not know the past. No ambition for the future.” I used that scene in class once, when teaching Arab Society, and the Egyptian students got the point straight away. It was like the movie was made for us!

You can’t build the future if you don’t realize that the present is a product of people engaging with the past. This means that understanding deeply that things don’t just happen by themselves. You have to make them happen. History isn’t haphazard and random. We understood these things at one point in time in Islamic history, at the time of Ibn Khaldun and Al-Maqrizi, but we’ve lost touch with that past awareness and found ourselves in the fix we’re in now. And I’d say this isn’t by accident, since the educational system and the curriculum for teaching isn’t determined by you or me but by the powers that be, and they are the ones who want you to live in the here and now, only, and forget the lessons of the past and the prospects of the future.

The trick, the good doctor clarified, is to be careful how you choose your periods because these categories are ultimately relative – they vary from country to country. What works one place doesn’t necessary fit somewhere else.

Now take a look at our part of the world. The masses don’t do any periodization, true enough, but intellectuals do. At the level of the intellectual elite we have a bizarre disconnect or divergence since the academics and journalists and opinion-makers use terminology on the periodization of history, taken verbatim from the West. Words like Middles Ages the Dark Age and the Renaissance. These are commendable terms in their own right but don’t match our history. I once got into an argument about this with some Egyptian friends, on the qahwa (قهوة), where they described our life now in Egypt being in a Dark Age phase. Naturally I laughed, since they’d clearly never heard of things like the Black Death and burning people at the stake and feudalism and serfs and peasants. Things are certainly bad but Egypt is a country that has satellites and running water in every house, so it’s not that bad. They were taking their personal plight, not being able to get a job with their certificates, and applying it to everything else!

Fortunately for me my education is Western to begin with and I had the added advantage of having taught a course called Scientific Thinking, which was all about the ancient Greeks and the scientific revolution. The truth is that periodization in European history itself is geographically and culturally misplaced, coming originally from ancient Greece. And is highly inaccurate even as far as Greek history is concerned. The Greeks were the first people to label eras in history with the terms Dark Age or Iron Age or Golden Age. But these terms were more moral than scientific – just ask Hesiod. Greeks actually continued to use bronze in the Iron Age and the Stone Age itself enjoyed a fair amount of metallurgy; copper, especially reinforced with arsenic, gold and even a little iron (from meteorites). And poets and bards saw history as a descending ladder, with the Golden Age and Heroic Age going downhill to the Bronze and then Iron Age. (Please see John Mansley Robinson, An Introduction to Early Greek Philosophy: The Chief Fragments and Ancient Testimony With Connecting Commentary, 1968). As for the Renaissance, which was the foregrounding for the Enlightenment, that itself resulted from an earlier period of progress that resulted from European contact with the Muslims, specially via Muslim Spain. And with that the revival of Aristotle, and Aristotelian rationalism and the social sciences, as well as the introduction of Arabic numerals. (Please see James Burke’s The Day The Universe Changed – S01E02 – In the Light of the Above and When the Moors Ruled in Europe: A Documentary by Bettany Hughes).

Therefore, instead of getting distracted by the Europeans periodizing their own history, what’s more important is to talk about the drivers for progress (القوى الفاعلة). And here I have to commend Dr. Walid Ali, a philosophy professor, for contributing during the virtual discussion. These are: transparency (الشفافيه), professionalism (الاحترافيه) and accountability (المحاسبيه).

This can’t be a top-down process, Dr. Walid added, noting that we have to embrace these factors if we’re ever to go from mere theorising about history to actually making progress in our history. I agree wholeheartedly and will add to that, but indirectly by going through some observations I made, in the comments section alone!

Arab Voices and Missing Variables

First of all, overrating the role of culture as a variable explaining the backwardness of a country. The classic response to this set of cultural explanations from the great social researcher in Egypt, El-Sayyid Yassin, in his book (الشخصية العربية بين مفهوم الذات وصورة الآخر). He argued, very rightly, that Egyptians culture was exactly the same in 1967 as it was in 1973, and yet in one year there was a crushing defeat and in the other a resounding victory!

Of course Mr Al-Yassin didn’t content himself with merely debunking Western notions of the Arab persona and Arabic mind. He provided an alternative explanation for all of the so-called characteristics of our culture and way of thinking – passivity, fatalism, lack of individual agency, unscientific way of approaching topics, etc.

His explanation, interestingly enough, was the second Abbasid era. In the Umayyads era you had great conquests and the growth of urbanity, and then in the Abbasid era, things got even better, with more city life and a commercial, moneyed economy. That means science and investment and technology and, critically, entrepreneurship.

Arabs are merchants originally, so this makes perfect sense. And then what happened? An internal collapse and backwards march, with Arabs becoming civil servants and bureaucrats, with a predatory junta taking over, making its money through feudalism and exorbitant taxes. It’s then that the Arabs fall into their fatalistic phase, learning to get along through being subservient to the state, even economically.

What went wrong? Obviously, the emergence of the Buyurid state in Iran, the first ever Shiite state, and their takeover of the Caliphate in Baghdad, turning the Caliph into a puppet. That’s when the Arabs fell out of the loop and stopped being in charge of their fate. Things only got worse afterwards when it came to the Turks taking over our part of the world.

So simple demographics, the changing composition of the Muslim population, and court politics and palace coups ruined everything. That’s when the Arab persona went into the negative, with people acclimatizing themselves to bad circumstances they were no longer in control of.

Watch The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and you’ll see how people socialize themselves to adverse circumstances, becoming so ‘institutionalized’ that they can’t readjust to life outside of prison even when they get parole. The prison is inside them. That’s what’s happened to us, on a macro-scale.

A second observation by yours truly which is the role of geography. When you talk about continuities in history and history repeating itself, you can’t chalk it all down to historical factors. We live in arid lands at the end of the day and that create extremes of one, over centralization, and extremes of the other – rapid decentralization, chaos, and tribalism.

Look at Egypt contrasted to Syria, or Sudan. The Ayyubids were in Egypt like they were in Syria, but they failed to impose the centralized system they had in Egypt in Syria, with the Ayyubids in Syria fracturing into warring city-states. It’s not just sectarianism, its geography. Syrians aren’t squeezed around the Nile valley to be regimented and easily controlled.

A third observation is the overemphasis on religion and the clergy. Economic historian Timur Kuran critiqued this tendency, or obsession, with Orientalists. They forget, for instance, entrepreneurs and businessmen and merchants, and other economic groups like peasants and the urban proletariat.

If you look at the Ayyubid era, again, you will find how cash-strapped Saladin was up against the Crusaders, with minimal armor, despite the fabulous wealth in the Near East at the time because of the trade routes. It seems all that money was beyond their reach, controlled by cliques of selfish merchants.

Europe by contrast, was mired in feudal poverty, the whole reason they left for the East, but the Crusaders had control of every penny in their impoverished European economies and so could afford the costs of total war. Now take a step further and look at successful examples in the Muslim world where entrepreneurs led the way, investing in industry and education and technology. We have, of course, Mahatir Muhammad in Malaysia, a businessman originally who was not content with redistributing wealth away from the Chinese capitalist class toward the majority of Muslim Malays but insisted on creating new wealth by creating Muslim Malay businessmen. But before him we had Talaat Harb in Egypt, a man who understood that business opportunities are created primarily through finance, which is why he set up the country’s first national bank and invested in everything from Um Khalthoum’s golden voice to shoe shops. He also set up the first textile factories, the synthetic silk factory to rival Japan, and Studio Masr as a forerunner of the movie industry and Egypt’s soft power reach. We’re still benefiting from him to this day, and he was an ultraconservative who was at loggerheads with Qasim Amin over women’s dress!

The point is its bottom-up progress, where economic variables are dragging the rest of society, and even the state, behind it. That’s essentially what happened in the West itself, with Gutenberg inventing the printing press as an entrepreneur as well as inventor, and Galileo patenting his telescope to the Venetian traders to better finance his scientific endeavors. Never mind the so-called journeys of discovery, again financed by Venetian traders, or the coal and steel revolutions and the steam-engine and the textile industries in Britain.

I can add, from my experience teaching Scientific Thinking, that getting progress going by itself creates a progressive frame of mind. You don’t have to have the intellectuals leading the herd. And with that, a progressive reading of history develops as people, yet again, acclimatize themselves to changing circumstances.

Again, look at Egypt, post-Muhammad Ali, with the likes of Taha Hussein, Qasim Amin and Abbas Al-Aqqad, names known across the Arab world and still the admiration of all. (Dr. Shakir Al-Makhzoumi mentioned this in the session). That didn’t come out of nowhere. Dr. Farouk Shusha was once interviewed on TV in Egypt and asked why we don’t have giants like Ihsan Abdel Qudus or Abbas al-Aqqad anymore and he wisely said that personal genius isn’t cumulative. Its (مفصلية), driven by turning points in history. When people feel their society is progressing, that there is a need for them, they rise to the occasion. They became the voice of the people and drive progress. Under normal or unremarkable circumstances, no matter how advantageous, intellectuals don’t take risks and try to rise above the rest.

A fourth observation is the role of history in history. That is, how we talk about and categorize and study the past, and meta-historical narratives, and how this plays a role in actual progress or regress. One of the reasons we’re in the fix we’re in that we take our historical categorizes and terminologies from the West, as stated above.

Here’s an interesting twist in the tale for us Egyptians. I attended a CEDEJ event once on the role of the French in modernising Egypt. (Amr Khairy, “Industrie and Al-Industriya: The Origins of Capitalism between Rifāʿa al-Tahtāwī and Saint-Simonian Engineers”, Centre d’études et de documentation économiques, juridiques et sociales, 22 October 2024). A lot of cultural and linguistic transference happened in that era so I asked about this annoying term we used in Egypt over and over again (مجتمع مدني), as if we never lived in cities before. (As if we were living in caves till we learned to speak French). They confirmed that his was some annoying phrasing in French that got translated literally into Arabic. And we’ve been stuck there ever since!

These insidious words and maladjusted concepts have made us reinterpret our history, to the point of selective amnesia, disregarding all of our history before this modernist era in the 19th century. If you cut yourself off from the past, you cut yourself off from the good things but also, critically, awareness of the causes of the bad things.

The whole problem we have, as I stated above, is that we’re consistently living in the here and now. Arabs, when they talk about accumulation, they talk about the accumulation of errors from the past, which is true. But there’s also accumulated lessons from the past as well, which sadly in our case doesn’t happen.

A Final Word

So, where to from here? Typically for me, I’ll end this article with the way I began it – science fiction. When I was in China in 2023, attending WorldCom in Chengdu, I witnessed with my own eyes how the Chinese regime was trying to create an entire generation of sci-fi fans, readers, and writers alike. The lectures we attended also explicitly incorporated science fiction as a driver for progress, because a country could never develop without genius and creativity and thinking outside the box. Science by itself couldn’t thrive without these component parts and science fiction was one of the best ways to do this. And it wasn’t just the central government in China that was promoting SF, but the provisional governments too. And the business class.

Dmitri Medvedev, when he was the Russian president, actually tried to pitch the entrepreneur as the driver of history while using science fiction as a representation of a futuristic information economy. (Please see Katri Pynnöniemi, “Science Fiction: President Medvedev’s campaign for Russia’s ‘Technological Modernization’”, Demokratizatsiya, 22, 2014, pp. 605-625). The presidential Commission for the Modernization and Technological Development of Russia’s Economy he set up was adamant to get Russia away from its dependence on the export of raw materials, exemplified by the oil pipeline. Science and entrepreneurship overlapped in this way of thinking and were the drivers for sustainable change and progress.

Sound familiar? That’s my recipe for success, along with not thinking in garbled French!